Kendo - The Way Of The Sword

THE TRADITION AND CULTURE OF THE SAMURAI

Kendō (剣道) is a modern Japanese martial art and athletic sport descended from kenjutsu (剣術), the ancient art of swordsmanship. Kendo stems from the culture and tradition of feudal Japan, grounded in the spirit of the famous samurai warriors.

Ken

(sword)

Dō

(teachings, path)

The characters that make up the word (Ken, Dō) indicate a discipline underpinned by ideals of self-improvement and respect. Aside from physical training, it encompasses the virtues of discipline, frugality, morality, and spirituality that formed the moral code of the samurai hundreds of years ago.

As a martial art, kendo helps develop self-awareness, self-control, respect for others, and a strong, focused spirit and mind, among other things.

Through the 19th and 20th centuries, kendo evolved into its modern form, including structured competitive matches and grading requirements, as well as safe armour and swords.

I want to swing a sword and hit people too!

While the concept of armoured sword duels may be exciting, kendo is quite different to Western swordfighting and fencing. Kendo places heavy emphasis on respect and tradition above all. Although often described as “Japanese fencing”, kendo differs from fencing in several ways:

Fencing weapons are one-handed and made of metal, while kendo weapons are (typically) two-handed and made of bamboo.

Fencing is restricted to forward-backward movement; kendo is not.

Points in competitive matches are granted electronically at a single touch in fencing, but in kendo, a valid strike must meet several complex criteria.

Kendo players, known as kendōka (剣道家), typically train in a purpose-built dojo, with wooden sprung flooring suitable for high-impact footwork. In countries without proper dojos, gymnasiums or sports halls are often used instead.

Kendo always "begins and ends with manners". A training session begins and ends with reishiki (礼式), where members line up, sit with their legs folded beneath them and enter a short state of meditation, followed by a series of bows to show respect and appreciation to the shomen (a shrine or flag at the front wall of the dojo), sensei (teacher), and otagai (each other). It is also important to show respect to your partner for training with you, as without an opponent, your sword is purposeless.

Training is usually instructed by the club’s sensei(s), where various exercises, drills, and sparring are conducted to develop proper technique, fitness, and focus.

Special protective armour, bōgu (防具), is worn during training and shiai (competitive matches) to allow players to make full contact without getting (too) hurt.

Kendo uniform and armour layering

Dōgi (道着) – a jacket with wide, elbow-length sleeves, fastened with two ties.

Hakama (袴) – long, pleated skirt-pants tied around the waist, allowing for free, yet hidden movement. The seven pleats (five on the front, two on the back) symbolise the seven virtues of martial arts - jin (benevolence, mercy), gi (righteousness, justice), rei (courtesy, etiquette), chi (wisdom, intelligence), shin (sincerity, integrity), chū (loyalty), and kō (piety).

Tare (垂れ) – a thick cloth belt with sturdy fabric flaps to protect the upper legs and groin from stray strikes.

Zekken (ゼッケン) – fabric drawn over the middle tare flap, embroidered with the wearer’s name kanji characters, and often their dojo/club/country (top) or English reading (bottom).

Dō (胴) – a hard breastplate traditionally made from lacquered bamboo, tied diagonally across the shoulders and back. Valid striking targets are slashing cuts from top to bottom to either side of the abdomen.

Tenugui (手拭い) – a simple, rectangular cotton handtowel wrapped around the head to absorb sweat and provide a comfortable base for the men.

Men (面) – a hard leather helmet with a metal grille (面金, men-gane) over the face and sturdy flaps to protect the throat, neck, and shoulders. Valid targets are strikes to the top of the head (either centrally or at a 45-degree angle) and thrusts to the throat.

Kote (小手) – thickly-padded, mitten-like gloves to protect the hands and forearms. Valid targets are the outer sides of each forearm, on the rigid cotton padding between the wrist and elbow.

Shinai (竹刀) – a two-handed practice sword made from four slats of bamboo, bound together by leather fittings and a cord. A donut-shaped handguard (tsuba, 鍔) is fitted onto the hilt, secured by a rubber ring (tsuba-dome, 鍔止め).

The complexities of a strike

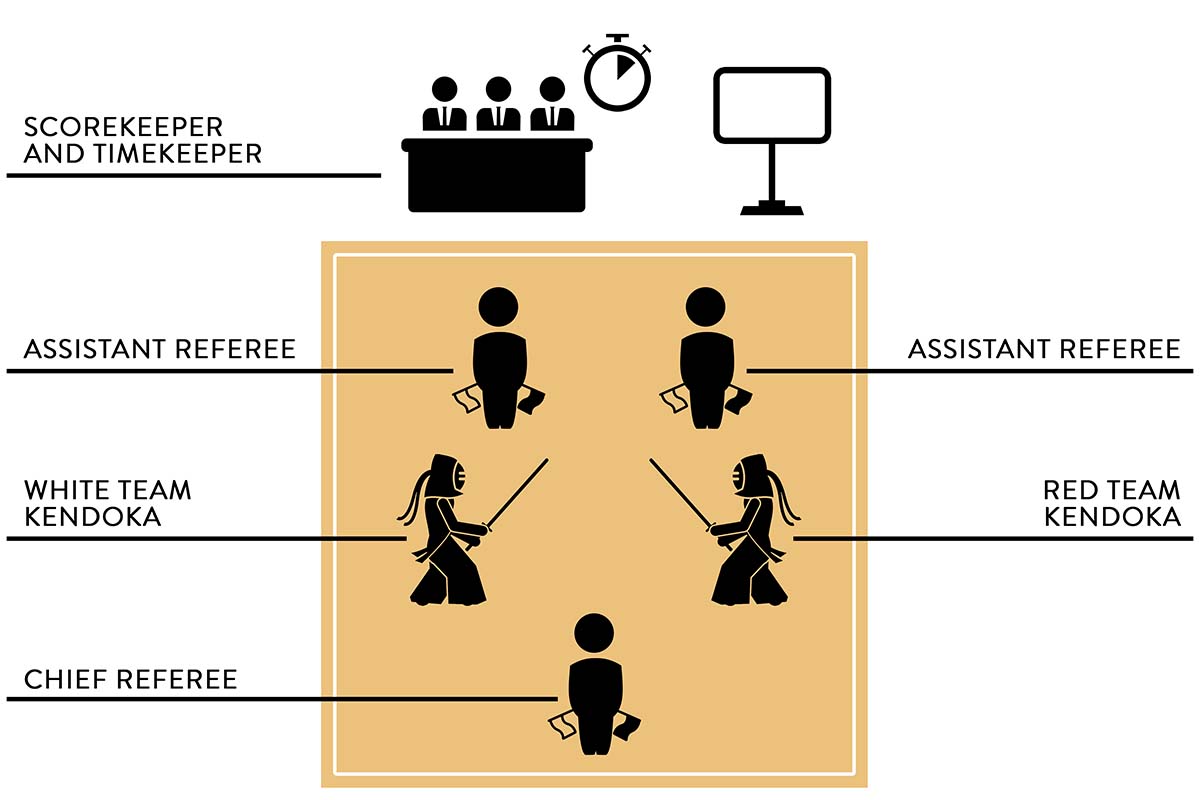

Competitions in kendo are always individual combats. Matches last 5 minutes and strikes are assessed by 3 referees in the square combat area. Matches are usually best-of-three.

In a kendo match, for a strike to be considered valid (ippon), it must meet several criteria; it must be made with correct spirit, hit a valid target, and be made with correct posture/movement. As such, the principle of “ki ken tai no icchi” – integration of your internal energy, sword, and body - is critical:

YAAH!

MEN!

(Hover over the kanji characters!)

Ki – the spirit, or internal energy

Ken – the sword

Tai – the body

(no) icchi – in synchronisation

Kendo gets quite noisy – to maintain a high level of internal energy, kendōka express their fighting spirit through the voice (kiai, 気合い), particularly during a strike, as you must declare where you are striking (demonstrating intention).

Strikes must be made towards specific armoured targets on the forearms (kote), head (men), or flank (dō), with the correct part and angle of the shinai. Tsuki, a thrust to the throat, is allowed only in high-level matches due to its dangerousness. Intentionally striking an unprotected part results in a penalty.

A stamp of the front foot upon striking (fumikomi-ashi, 踏み込み足) is executed to improve power and emphasise the intention of the hit, as shinai strikes are often very swift. Additionally, the way you behave both during and after the strike is something the referees watch for - maintaining appropriate posture and showing "zanshin" (continued readiness and awareness after striking) is crucial.

These elements are evaluated by the referees in a match – if at least two of the three referees raise their flag, a point is awarded.

See if you can spot these things in the videos below!

Kendo around the world

Although kendo is still offered in many secondary schools across Japan as a form of physical education, the number of kendōka in Japan is slowly decreasing. Knowledgeable sensei are ageing, and kendo’s strong emphasis on respect, self-discipline, and tradition may make it difficult for the art to survive with our fast-changing societies. On the upside, kendo is steadily gaining popularity worldwide – the 19th World Kendo Championships were recently held in July in Italy, where kendōka from around the world engaged in international competition and cultural exchange.

In Australia, there are many quality kendo clubs, typically university sport clubs, where you can learn and see kendo in action. Annual state and national competitions provide opportunities for players of various levels to compete and improve.

Although kendo may now be a sport, it is still a "do" - a way of the samurai. It is a sport that trains the spirit, skills, and physique, while reflecting the traditions of Japan – kendo is not only incredibly fun, but also a path of lifelong learning and self-improvement! Give kendo a try!